Berlin: A Childhood of Light and Shadow.

Chapter 2

We are all born into mystery, but some of us face its sharp edges earlier than others.

Chapter 2

My name is Aida Smajic. I have been thinking about why I am here since I was about six years old, when I realized we were floating in an infinite space and that my parents were not always going to be there. I have been aware of the mystery of human existence since this very thought sank into my bones and became a part of me. The more I thought about it, the more questions and uncertainty I felt as a child. I remember then, so young, looking at both of my parents and sobbing at the notion that either nothing—or everything—was forever. We all exist as points somewhere along the timeline that is life. You know when it begins, but you don’t get to know when it stops. Everything held so much meaning for me because of this.

Life was going to be lived one way or another, and the only certainty I had was that time would be the force guiding it into the one direction we’re all going. We’re all destined for the same end path. We’re born, we make choices along the way, we suffer, we win at times, cry many times, laugh at times, and then it is over. Life is such a precious gift, I thought—what a beautiful creation. There was no escaping this truth.

We all cling to the things we hold true in order to navigate this world. What are your truths? This is the question that took me years to answer, with many hard lessons.

I was born in Brčko, in the beautiful country of Bosnia & Herzegovina. At the age of two, my family fled the Civil War arising from ethnic tension between the Bosnians and the Serbs in 1992. My life was forever changed—our lives were forever changed. Certainty of life as it was once imagined became nonexistent. I would never know what it’s like to grow up in the home my father built for us, and I would never know what it’s like to be taken care of by my grandparents. We were not certain of where we were going when we left, but staying was not an option. My father came close to death in a concentration camp when he was captured. By divine intervention, he was recognized by a Serbian soldier inside the camp—who happened to be his friend—and was released from what could have been an unfortunate ending. We escaped together as a family. We never looked back, because we couldn’t. Out was the only way if we were all going to make it.

Brcko, Bosnia - 1992.

One of the few photographs preserved from living in our house in Brčko. The war in Bosnia and its occupation started not long after this photo was taken.

After months of running from the tragedy that was only getting worse, with refugee status, my haven and home became Berlin, Germany. For the next seven years, I would spend my childhood growing up in various state-funded apartments on the east side of Berlin, speaking and thinking in German. The very last train stop took you to Lichtenberg; this is where I remember my memory taking shape. I didn’t have any memories from Bosnia because I was too little. My name was Aida Smajic. I was three years old when I moved to this world. I assimilated. I played my new role well. I was fortunate to have my family—that was enough.

Growing up in Berlin as a child had deeply memorable and profound moments for me. I cannot recall many memories from the time we fled Bosnia to the time we settled in Berlin. What does crash into memory is hiding in a bathroom stall at a bus station, hiding from the authorities whose footsteps I could hear circling us. I remember looking at my mother, so young, and her signaling with her index finger to her mouth to be quiet. I understood. The footsteps ceased, and we were on our way. We ended up in Switzerland, Poland, and Denmark before we made it to Germany. In Poland, a scene replays in my head where I am learning to play chess with the help of my father and another man who was also a refugee. This was in a hotel that housed us for safety. This man had a son, who was around my age. I will forever remember his face, but I could never recall his name. He followed me everywhere and wanted to be friends with me. I was fearful of him; I had already begun building a wall around myself to not let others get close to me. This was the first friendship, the first relationship with another human, that lies embroidered in my memory. It foreshadowed how I would handle future relationships. I did not like people getting close to me, for I feared they would leave me too. From early on, the things that were dear to me were constantly being taken, and this was my safety measure—not getting attached to others, because people, places, and things were not stable or constant.

And yet, I was a happy child. I loved sports. My sister and I filled our days with gymnastics, running, high jump, long jump, and table tennis.

One of the greatest influences of my childhood was my first-grade teacher, Frau Lanzke. She was extraordinary. When I entered school in Berlin, I was fortunate to have a teacher who cared for me deeply, and to this day, I remember her. am certain that my belief in myself would have been profoundly different without her. As a child, I saw pain, wrongdoing, confusion, mistrust, and blame all around me. She gave me none of that. She saw my heart, though it already carried misfortune. She understood that my reserved nature was not defiance, but fear—fear of being ridiculed for not belonging. It was hard to feel accepted when my own country had not accepted me. It was here that the notion of being “the other” was born, and I could not escape it.

Frau Lanzke and I attended the second-grade induction celebration at the elementary school in Berlin, Germany.

Presenting in front of my classmates alongside Frau Lanzke.

I had many German friends, as well as many Bosnian friends. As kids, the relationships that I did have were souls who understood struggle from their own lives. We found refuge in our loneliness, but we never spoke of it. We went on being reckless little kids—playing catch, digging holes in the dirt, and stealing delicious fruits from nearby trees as we explored our new world. We were misfits, but we played by the rules. Days filled with scraped knees and elbows from running around the neighborhood were days we knew we had truly lived. The life we had was beautiful because we made it so in our minds, using our imagination and playing games to escape reality.

These were the best friends who lived in the same refugee housing with us and had identical reasons for being there - war displacement.

Outside of our walls, I ran into problems that made me feel shame for having an identity that did not belong with the country’s name. Not everyone was against us. Frau Lanzke believed in me. I think of her often, alongside the other brilliant teachers who came into my life—I owe them my life. They taught me the importance of hard work, learning, and striving despite the odds. They could try to tear me down, but a mind seeking knowledge was untamable. From first grade until fourth, when I left my second home, I continued to be a good student inside the classroom walls.

Not everyone was as welcoming. In second grade, while playing on the monkey bars at school, a boy from my class reminded me that I was supposedly abusing government resources by living as a refugee, as if I had willingly made that choice. We were so young, and yet what was ultimately a normal circumstance was twisted into an attack. I did not cry. I told him this was not my fault. I never fought back, because the truth was we were lucky to have this haven and I did not want to give him reason to think otherwise.

I became brutally aware of my situation again in third grade. After German reading class, we were given thirty minutes for recess. All the kids rushed outside to enjoy the expansive school grounds, which included paths for running, a wooded area, and a large backyard with a playground and ping-pong tables. Trauma did not end with the war; sometimes it lived in my head, in others’ commentary, and in my own reflection.

Here, playing outside with my friends, I faced the single most ruthless experience of my time in Berlin. Living among mentally unstable people in refugee housing, finding syringes on the floor, or even hearing a gunshot while climbing trees were manageable. But during one fateful day at recess, I was traumatized in a way I could not have anticipated.

It was my turn to play a game of hopscotch, a game we had chalked ourselves. Some German girls occupying the space refused to let us have our turn. Through diplomacy and fairness, we convinced them to let us play. The bell rang, recess was over, and we returned to class, sweaty and happy.

I sat in the back, my desk neighbor absent. Our teacher began speaking—not about the lesson, but about what had just happened outside. I realized she was talking about me. She lectured the class on how it was unacceptable to take something that did not belong to me, implying that my polite request to play had overstepped some invisible boundary. Time slowed. For forty minutes, I sat under her scrutiny as she flailed her arms, demonstrating what it felt like to not have a right to comfort. She sat atop my desk until the bell released me, leaving me humiliated, ostracized, and powerless. I was alone in shame, a child trying to fit into a world that celebrated homogeneity.

Saved by the bell, I ran home, tears weighing me down, leaving behind a trail of despair. My parents knew something terrible had happened. I refused to go to school for a week, too scared to face that altered reality. Eventually, I was summoned to the school principal a man of character, who heard my side and apologized on her behalf. He offered a space where I was heard and understood. While the teacher left a mark on my exterior, she unknowingly prepared me for the challenges ahead.

I went on to enjoy my childhood, relishing the diversity Berlin offered. Can you imagine the freedom I felt as a kid in that city? The trains took me all over Europe, and history, scenery, and adventure were at my fingertips. We never went hungry. My parents provided everything my sister and I needed, shielding us from scarcity and nurturing our ability to bloom.

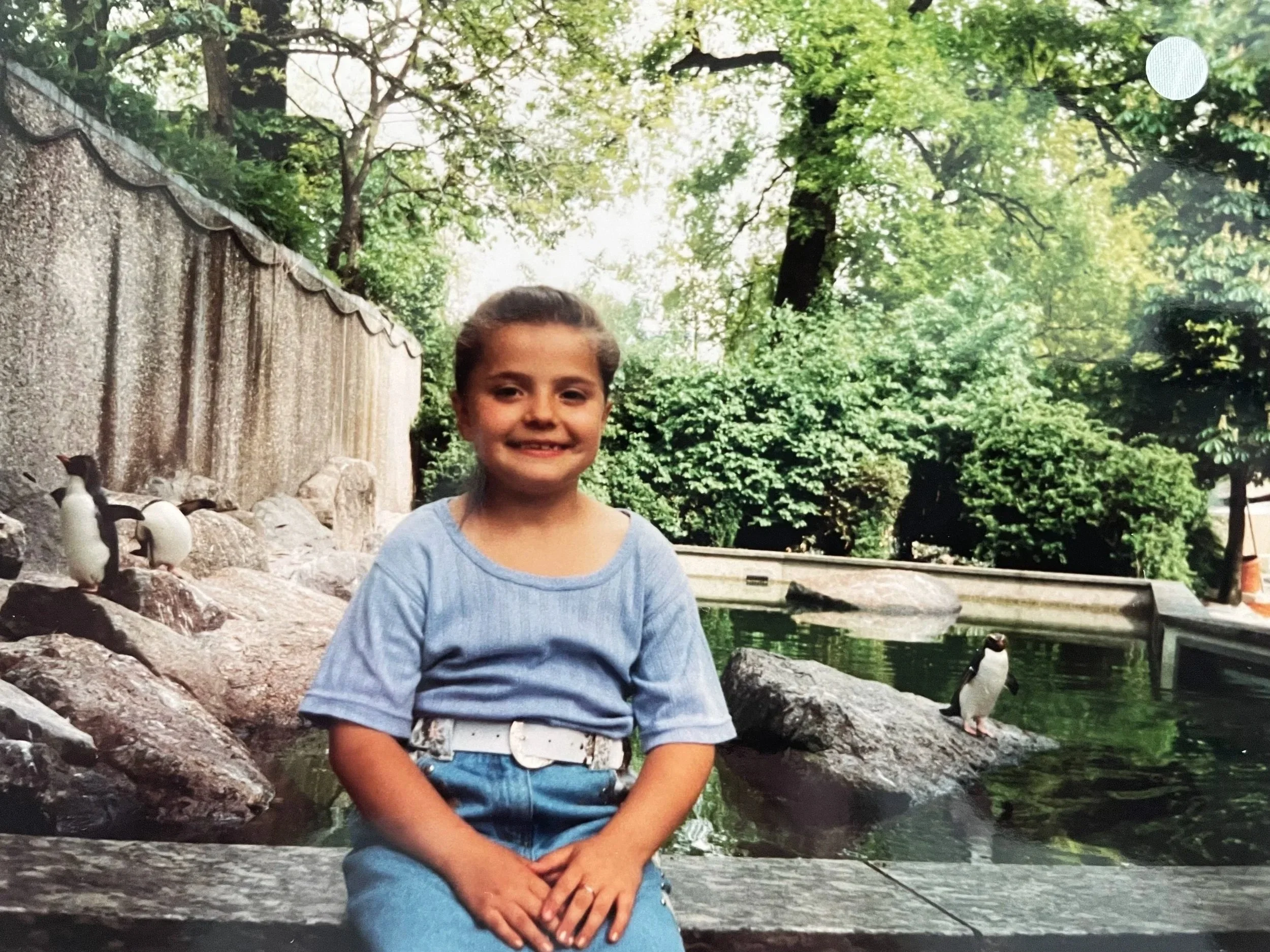

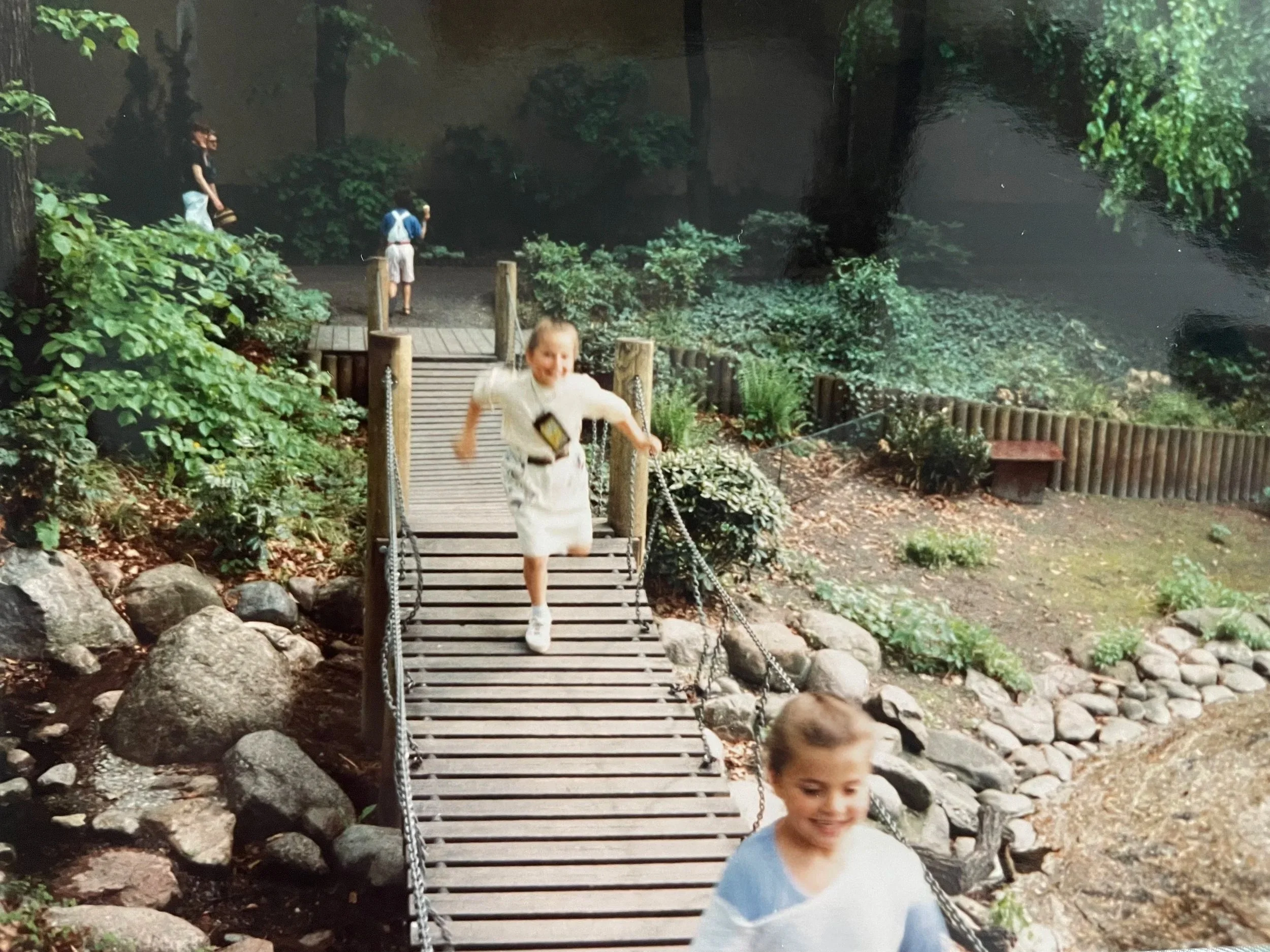

I remember trips to parks, international farmers markets, the zoo, bowling alleys, mandatory Döner stops, Christmas light shopping, and circus performances. We had a normal childhood, though my parents struggled more than they let us see. My mother once sobbed at the kitchen table over another move, from an apartment we didn’t have to share to one like a dormitory, with shared kitchen and bath. Her strength and grace were extraordinary, keeping us afloat while she bore her own burden. She loved us more than anything and made us believe we had the world.

At the Berlin Zoo our parents would often take us to. Behind me a flock of Penguins and I proudly sitting in front of them.

Running down the bridge at the Zoo, making a connective memory together.

On top of regular school, my parents sent me to Bosnian school twice a week for two years. I resisted at first, but it preserved my ability to speak and write my native language fluently. The teachers were strict, calling on students to recite poetry without warning. The pressure ignited a discipline in me that stuck. My thoughts, actions, and interests had become German, but the Bosnian program kept my roots alive. One of the ways my parents lured me into going to the extracurricular Bosnian school was to tempt me with a Döner after it. I looked forward to that Döner more than anything.

I’m standing next to my favorite Döner kiosk with my dad not far from our home in Berlin. This is how my parents would bribe me with to attend Bosnian schooling on top of my regular school hours. They made the best Döner in town.

Growing up as a refugee in Germany was a blessing in disguise. At such a young age, I didn’t have time to dwell on identity or displacement. Minor cracks appeared, but I bounced back. Resilience was born, practiced, and developed in these experiences. Side-handed comments, conservative neighbors, unstable apartments—all of it contributed to growth.

I was an odd child, competitive and curious, moving between friend groups and interests freely. I delighted in winning, outsmarting, and defying the odds. Some friends bullied me, yet these moments shaped my cunning and courage. One of my greatest childhood achievements came days before we left for America. My sister and I joined a German table tennis club and trained tirelessly. Weeks later, we won our age division, claiming the championship trophy. It was a moment of unexpected glory, a shared triumph with my sister that I will never forget.

Singing German songs with my classmates to celebrate the start of the new school year.

Our childhood was not easy, but the love of our parents and the friendships we built made it rich. We were outsiders in a world built for others, yet we wove our own make-believe world, finding joy in the simple pleasures. Berlin gave me home, freedom, and a mindset of universal introspection. We were too free then to know the limits imposed by adults. I learned early how fragile attachment is and how cruel exclusion can feel.

I lived in East Berlin until I was ten years old. Germany was my home. It shaped my early identity, my language, my friendships, and the first pieces of who I was to become. But when our refugee status expired, we were told we had to leave. After seven years, our asylum status ran out, and my parents applied for the United States. Again, my life was uprooted. With two suitcases and my parents by my side, we boarded a plane to America. The uncertainty began all over again.

On July 13th, 1999, we said goodbye to Germany. I was ten, my sister twelve. I did not want to leave. I loved being a kid in Berlin. Boarding the train, I held my walkman, wearing brown khaki shorts with large side pockets, and a striped shirt, staring out at a home I was leaving behind. America awaited—unknown and untested.

This photo was taken on July 13th, 1999. Our best friends Elvisa and Anisa wanted to send us off so they went to the train station with us as we departed to America.

Four months after resettling in our new surroundings, I had become fluent in English. I had always been a good student, and I knew that learning the language was the first step in survival, just as it had been when I arrived in Berlin just 7 years prior.

My world changed when I asked for guidance and strength. Life’s lessons came fast and sometimes darkly, but I realized I could choose a lighter, easier, and more joyful narrative. I lost myself for a while, but through suffering, reflection, and effort, I rediscovered myself.

We have intellect, suffering, and choice. Every day offers the opportunity to recreate ourselves. Life is short, and the choices we make accumulate. Pursue beauty, seek joy, and avoid what does not serve you. Life is a journey of conscious decisions, of learning from mistakes, of growing through hardship. Even when the world around us challenges us, the inner voice of reason guides us if we listen.

Time remains the constant in a life of change. My story, intimately known to me, is now ready to be shared—to help others process the past, move forward, and find a wondrous perspective on their own lives. Life is meant to be lived and enjoyed. And in sharing, perhaps others can see the light that I found, even in the shadows.

Looking back now, I know that my story is not only one of tragedy. It is also a story of resilience, of hope, and of love. It is the story of survival against the odds. It is the story of the questions that kept me awake at night, the tears that came uninvited, the laughter that surprised me, and the deep sense of wonder that has never left me.

The sharp edges of mystery cut into me early, but they also carved out a strength I would need for the journey ahead.